Protecting Our Creativity

From the most talented artists to those of us who are just beginning to re-engage with our imagination, we all have creative endeavors that are in fragile states. Inner and outer forces may pressure us to share those fragile pieces of inspiration with others and with the broader world. This post addresses the topic of what makes creativity fragile, as well as how and when to let our vulnerable creativity out of a protective space.

Creativity and Fragility

Creativity is not just an aspect of the arts; in fact, we can exercise creativity in almost any realm of human experience, from cooking to organizing, and from parenting to our professional lives. We can all most likely think of certain realms, however, in which our creative expression is very fragile and others in which it is less so.

Not all manifestations of creativity are fragile, and many factors influence this. One is experience. The longer we have been involved with a particular form of creativity, the less likely the output is to be delicate. A beginning woodwork’s craft, for example, is bound to be more fragile than a seasoned one’s.

Another aspect that might affect the fragility of a piece of creativity is the extent to which we identify ourselves with our creations. In this realm, we might ask ourselves which is the fragile entity: the creation (the thing created), the creativity (the inherent ability) or the creator (the person). Why is this such a difficult question to answer?

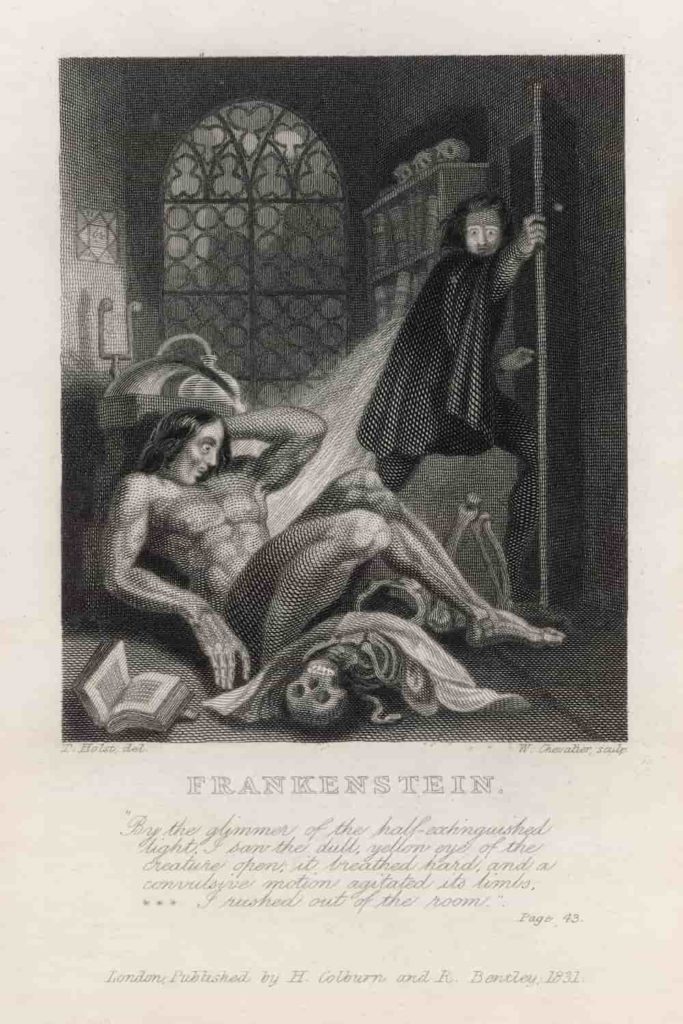

The line between the creator and the creation has constantly caused confusion in our culture. An example is the commonplace inclination to refer to creative output as the children or offspring of their creators. Miguel de Cervantes, the famous Spanish writer, comments on this tendency in the prologue to his novel Don Quijote (although in this case, the author claims to be the stepfather of his creation, as he takes only partial credit for the novel’s parentage). Another literary example that has entered popular culture comes from Mary Shelly’s novel Frankenstein. In the popular imagination, we often think of the monster created by Dr. Victor Frankenstein as Frankenstein (in other words, we use the name of the creator to designate the creation/creature). There are countless other related examples, and such a close connection between creator and the created seems to be a cultural commonplace. The more we identify with our creations, the more likely we are to be protective of them or to see them as fragile.

Whether it springs from levels of experience or levels of identification, we instinctively know that there are some creations that we as creators feel the need to protect more than others.

Respecting Boundaries

Part of determining how and when to share our still fragile creative output is understanding who the appropriate initial audience may be. In other words, how do we determine who gets to partake in our still vulnerable creativity?

In setting boundaries around creativity, problems often arise when we confuse overall emotional closeness with appropriate limits specific to creativity. We may be generally very close to a particular person, such as a spouse or partner, a child, a parent, a sibling, etc., but that doesn’t mean that this person is the best person with whom to share our still fragile creation. Respecting limits around our creativity (i.e. understanding what others and we ourselves can handle in regard to our creativity) is a way of safeguarding relationships.

Here is a list of questions to ask ourselves regarding whether a particular person is a safe audience with whom to share our still fragile creative endeavor:

- Does this person have an open mindset regarding our particular area of creativity?

- Does the person understand our current level of proficiency (novice or otherwise) within this area?

- Is this person able to provide constructive feedback to us about this realm of creativity?

- Is the person capable of being supportive of us as creators even though they may critique our creative product?

- Are we capable of accepting constructive feedback about the creative product from this person and not take it as a critique of ourselves, the creators?

Not entrusting our fragile creative output to someone doesn’t mean that we don’t care about them; it is rather a way of safeguarding the creation, as well as the relationship. This is compassionate if it protects both parties from an interaction that might not be productive. It also does not mean that we will never share this aspect of our creativity with this person, it just means that we judiciously chose an appropriate time for us, for them, and for the creative endeavor.

Letting Go

Up until this point, this post has been a reassurance that it is okay to protect our still fragile creativity. It has explored why a particular creative endeavor might be fragile, and what might the clues be about who is a good initial audience. I would argue, however, that the time for being protective of our creativity ought to be limited. At some point, it will be time to let that imaginative output out into wider spheres.

Many of us hold back our creative production from the world out of perfectionism. We think that if we tinker or edit enough, there will come a time when the product is perfect. I have very rarely come across a perfect painting, or a perfect academic paper, or a perfectly decorated house, or a perfectly prepared meal, or a perfectly raised child. Perfection is overrated. Accepting our own imperfections and those in our creations are important first steps in being compassionate to others when they fall short of our creative ideals. Perhaps if we all practiced putting our creativity out into the world and accepting the imaginative potential in others, the world would be a more compassionate and creative place.

Not everyone will understand or appreciate our creative output, whether it is in the realm of music, business, teaching, or sculpting. It is always an option to keep our creative potential to ourselves and never open it up to being critiqued by the outside world. But if we attain enjoyment from our creations, then chances are that others will as well. Is it wise or compassionate to deprive the world of enjoying what makes each one of us uniquely creative?